Armita Geravand : suppression of rage and grief

Only 17, Armita is the latest victim of the gender apartheid regime governing Iran. She was buried under heavy security yesterday after a month of being in a coma.

Only a few days after the one-year anniversary of Mahsa Jina Amini’s killing, on October 1st, Armita Geravand was riding the Tehran metro with some school friends without the mandatory hijab when, following a presumed altercation with hijab patrols, she was taken to the hospital unconscious. Armita was in a coma for 28 days, during which time contradictory accounts of what had happened to her started to take root, in parallel with the heavy censorship and gag order imposed on reporters and Armita’s family trying to inform about her condition. The official narrative was simple: Armita’s blood pressure suddenly dropped, causing her to fall and hit her head somewhere in the train wagon and lose consciousness, she was taken to the hospital where it was determined that she hit her head so hard that she was now in a coma. The Iranian state TV even did an interview early on with Armita’s parents who, clearly in shock and horror of the state they found their daughter in, repeated the claims: ‘Apparently her blood pressure dropped, … that’s what we have been told … we don’t really know’. The official investigation barely revealed any new information - a documentary aired on state TV showed a selection of CCTV footage cherry-picked to show Armita’s route to the metro, with blank spots and time jumps. The public frustration with the botched investigation was answered with false claims that there were limited number of cameras in the station, and none inside the wagon. All this as eyewitness accounts told a very different story.

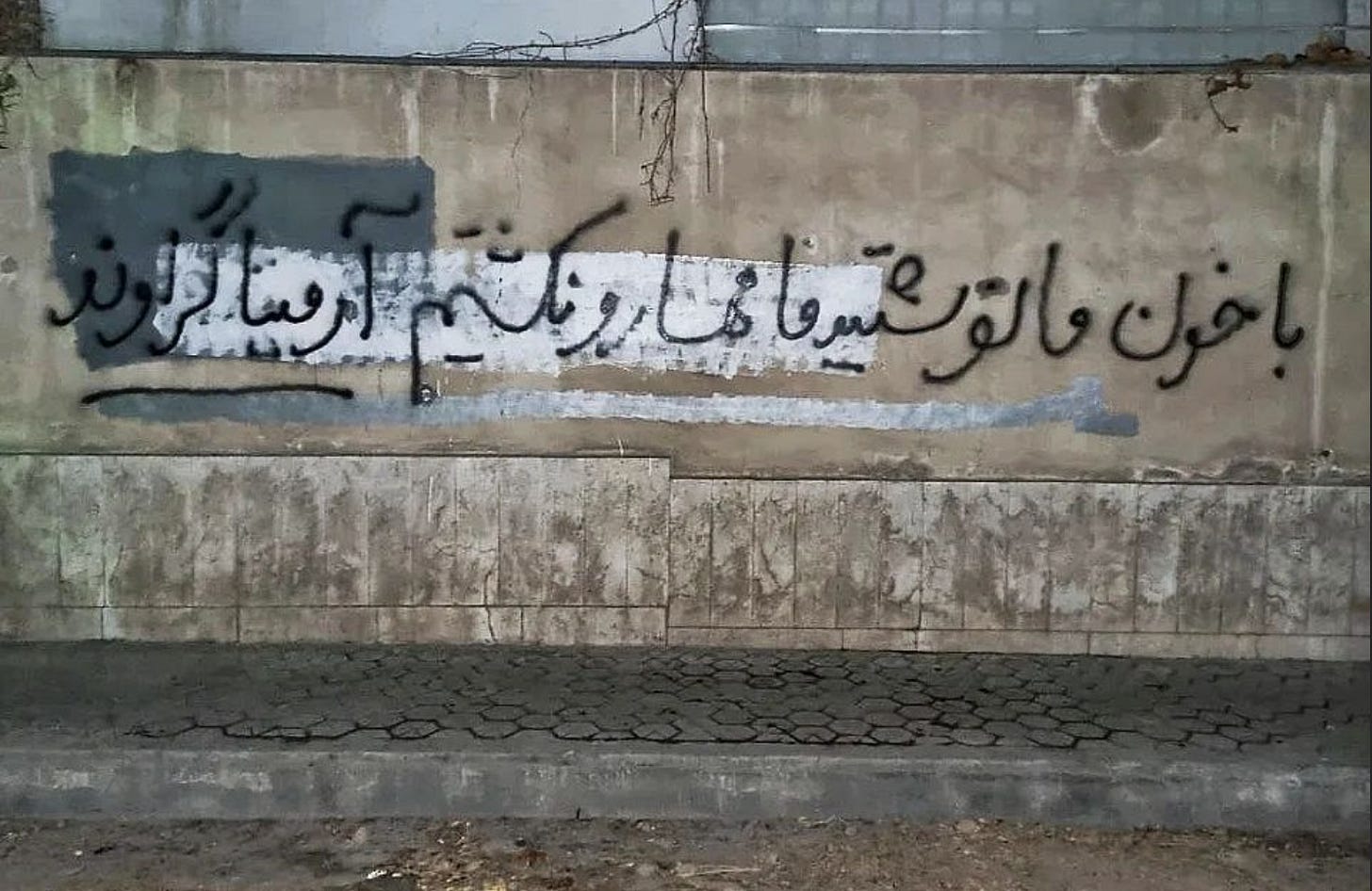

One can begin to understand the rage and fury directed at the state and such narratives it propagates when these efforts are seen in the context of the past year (for the sake of our own sanity, it is wiser to limit the reflection to the past year, though this practice is much older and the rage much more deeply rooted). The same apparatus was at work when, following Mahsa Jina Amini’s killing, state-sponsored documentaries attributed the cause of her death to a pre-existing condition which, although dormant for practically all her life, was suddenly activated when she was in police custody and took her life, using cropped CCTV footage to back up their claims. In the uprising that followed, cameras everywhere were weaponised against protesters - including those inside metro wagons, indeed the same make and model as the one Armita was riding. The same cameras were covered with menstrual pads to stop them identifying women refusing to wear the hijab, or otherwise voicing their protests during their commutes. To add insult to injury, pictures from Armita’s funeral showed multiple cameras installed around her grave - the all-observing omnipresent eyes of power watching you even in your grave, if it so chooses.

There is much to be said about the use of CCTV cameras and their use in authoritarian systems - about the irony of their installation with a promise of safety and security for citizens, and their cherry-picked use to oppress citizens and safeguard the interest of those in power. But within the broader issue of narratives and construction of reality, CCTV cameras and footages are just one piece of the puzzle, utilised for the broader aim of sowing confusion and distrust, rendering the population unable to see a route to the truth and consequently dampening the emotional response and reaction to the state of affairs in the country. For each narrative of injustice and suffering, there is a counter-narrative of apolitical accidents and patriotic neutralising of enemies of the state. Within this context, the value of life itself is not equally distributed - there are lives for whom investigations are thorough, and CCTV footage abundant, mourning ceremonies granted, and perpetrators swiftly brought to justice. While for others, their ‘death’ is deemed accidental and barely worthy of professional investigation (in any case futile given the absence of CCTV footage), their lives are conceived of un-grieveable and their memories undeserving of commemoration, naturally nobody is ever punished for such deaths. Armita’s funeral was held under heavy security and many in attendance were beaten and taken into custody for their presence there - in line with arrests and threats against families of those killed in the past year, barring them from holding ceremonies in memory of their loved ones.

In the past few weeks, watching the construction and erasure of narratives around Armita’s ordeal, it is plainly visible how the Islamic Republic manages and manipulates popular responses to the atrocities it commits - on an individual emotional level, and consequently regards possibilities for collective action. It tries to dilute and dissipate the rage and anger following yet another blatant injustice and suffering, by controlling the flow of information: both in terms of which pieces of information make it to the public view, and crucially how and by what means these are propagated in the public discourse. The trickling of incomplete information engenders a sense of hopelessness about the very possibility of uncovering the full truth, and with it the possibility of acknowledgement and compensation for the harm caused. Oppressing the very act of grieving and mourning further perpetuates this impossibility and carries it into the future - for in the absence of a reliable historical record, and with a concerted effort at erasing traces of injustices, even in the public memory, little resources remain for future restoration of justice. One must also not forget that injustices in a system like Iran are a constant fact of life and people are constantly bombarded with news of new instances of suffering, so much so that even keeping a personal record of them is an immense task. In the weeks that Armita was in a coma and Iranians had collectively held their breath hoping she would recover while knowing it to be an improbable prospect, lengthy sentences were handed down to journalists who reported on Mahsa Amini’s killing; more academics were expelled from their university posts for supporting student protests; anti-Afghan racism took the life of at least one Afghan worker in the country; and a famous filmmaker was brutally murdered alongside his wife in their family home.

These tactics are not unique to the Iranian regime and are instead echoed in various ideological regimes, missions, and wars. Indeed they are visible currently in the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine. I have been grappling with the question of writing about the regional conflict from the perspective of an Iranian, in a space dedicated to Iranian experiences and grievances. But when I write these lines about management of emotions, about construction of narratives that render some lives more valuable and worthy of grief, while others are dismissed as accidental or simply a price to pay for a particular vision of the future, the boundaries of the subject I am writing about start to blur. This might be where different ideological ways of seeing the world and narrating its realities converge: in building a hierarchy of value of life and managing popular emotions accordingly, in order to bring about a desirable state of affairs. The Islamic Regime devalues lives of protesters, dissenters, and non-ideal citizens inside the country. It devalues the lives of its imagined enemies like Israeli citizens, when it organises a celebratory gathering following its ideological bedfellows, Hamas’ attack on Israel. In its efforts at justifying the war, the ideological state of Israel similarly devalues the lives of Palestinians by equating them with Hamas and rendering them unworthy of sympathy, grief, or reprieve. The official narrative in Iran encourages empathy only for those aligned with its own values, lifestyle, and way of seeing the world - the ‘ideal’ citizens. The official narrative of war between Israel and Palestine, fails to even mention Palestine by name, claiming a monopoly on moral standards and consequently demand unequivocal, unconditional support for collective punishment of people who are seen as unworthy of empathy, justice, or grief.

These parallels are not lost on that section of the Iranian population that, fighting the pervasive construction of hierarchy of human value, sees the different manifestation of the same fundamental form of oppression in different contexts. Following the explosion at Al-Ahli hospital in Gaza that killed hundreds, and the unbelievable lack of evidence and accountability of the perpetrators, an Iranian user posted on social media with a simple statement that demonstrated the shared injustice inflicting the two peoples: “it is as if all CCTVs in the Middle East have broken down”.